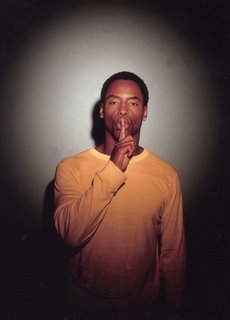

Walter Mosley: 'The Man in My Basement'

Race, Power, Good and Evil on Display in Author's Latest

All Things Considered, April 25, 2004 · Walter Mosley's latest novel, The Man in My Basement, examines race, power and identity -- core subjects of much of his past work. But this time he has even more fundamental mysteries in mind.

"I wanted to show a meeting between evil and innocence," he tells NPR's Cheryl Corley during a discussion of his book and its underlying themes.

Race, Power, Good and Evil on Display in Author's Latest

All Things Considered, April 25, 2004 · Walter Mosley's latest novel, The Man in My Basement, examines race, power and identity -- core subjects of much of his past work. But this time he has even more fundamental mysteries in mind.

"I wanted to show a meeting between evil and innocence," he tells NPR's Cheryl Corley during a discussion of his book and its underlying themes.

Mosley pursues that goal by matching two characters whose lives are worlds apart.

Charles Blakey, the protagonist, is an African-American slacker who has lived a directionless life since being fired from his latest job. One day, Anniston Bennett, a wealthy, 57-year-old WASP, appears at Charles' doorstep and offers $50,000 to rent his basement for the summer. But there are a few conditions:

As a kind of self-punishment, Bennett transforms the basement into a locked cage. And an experimental relationship unfolds with Bennett playing the role of a white prisoner, with Blakey as his black jailer.

Mosley uses the mock prison-cell setting to play with the dynamics of race, freedom and manipulation. In exploring those topics, he gives a nod to classic existentialist novels of the past.

Charles Blakey, the protagonist, is an African-American slacker who has lived a directionless life since being fired from his latest job. One day, Anniston Bennett, a wealthy, 57-year-old WASP, appears at Charles' doorstep and offers $50,000 to rent his basement for the summer. But there are a few conditions:

As a kind of self-punishment, Bennett transforms the basement into a locked cage. And an experimental relationship unfolds with Bennett playing the role of a white prisoner, with Blakey as his black jailer.

Mosley uses the mock prison-cell setting to play with the dynamics of race, freedom and manipulation. In exploring those topics, he gives a nod to classic existentialist novels of the past.

The Man in My Basement

by Walter Mosley

(Serpent's Tail, £7.99)

Mosley is primarily known as the writer of the Easy Rawlins detective series, the first of which is set in postwar Los Angeles and which extends, in the latest, to the 1960s. President Clinton's enthusiasm for Mosley, expressed in 1992 (when he had just two novels under his belt and had published the first Rawlins book only two years before), reflected fairly well on both of them - for whatever else you might have thought about Clinton, no one ever said he was stupid. (Ah, how far off those days seem.) Clinton also had a better affinity with black Americans than just about any other president, and this seemed like one of the facets of that affinity. It was also pretty good news for Mosley, who has since been able to hop genres and not feel the need to confine himself to the detective story, however at home he was there - people have compared him to Raymond Chandler, and not just because Rawlins was based in LA.

Mosley has always, obviously, been finely attuned to matters of race; but he has also been interested in evil, or warped morality. Here the two concerns come together in a most bizarre and fascinating novel.

Our hero and narrator is Charles Blakey, a young black man who lives, perhaps improbably, in a 200-year-old house in (I think) Connecticut. It's in, as he puts it, "a secluded colored neighborhood", and while his house may be large and ancient, Blakey himself is coming apart at the seams: he is a shiftless, already washed-up man who can't hold down a job, drinks too much, alienates his friends with his puerile behaviour and, without handouts from his increasingly intolerant aunt, would lose the home that has been in his family for generations.

Our hero and narrator is Charles Blakey, a young black man who lives, perhaps improbably, in a 200-year-old house in (I think) Connecticut. It's in, as he puts it, "a secluded colored neighborhood", and while his house may be large and ancient, Blakey himself is coming apart at the seams: he is a shiftless, already washed-up man who can't hold down a job, drinks too much, alienates his friends with his puerile behaviour and, without handouts from his increasingly intolerant aunt, would lose the home that has been in his family for generations.

This picture of a man trapped by his own helpless indolence rings true; you feel that only a miracle, or a deus ex machina, could save him, and one arrives: a "small, bald-headed white man" (Serpent's Tail wisely does not reproduce the cover of the US Little, Brown edition, which appears to show, puzzlingly, a slightly built white man with a full head of hair), who offers him a huge sum of money to keep him imprisoned in his basement for a couple of months.

This picture of a man trapped by his own helpless indolence rings true; you feel that only a miracle, or a deus ex machina, could save him, and one arrives: a "small, bald-headed white man" (Serpent's Tail wisely does not reproduce the cover of the US Little, Brown edition, which appears to show, puzzlingly, a slightly built white man with a full head of hair), who offers him a huge sum of money to keep him imprisoned in his basement for a couple of months.

It isn't until about halfway through the novel that the white man, Anniston Bennet, arrives for his incarceration. Until then we have had enough to be getting on with: Blakey's gradual decline, and then his determination to clean out the house, revealing centuries' worth of history. This is in itself a kind of redemption - a word Mosley pays particular attention to in the novel's closing pages - but Blakey still has some way to go.

Bennet turns out to be one of the world's unseen powerful men, maybe not evil in himself but in no way good and certainly a conduit for evil: "a precision tool", he puts it, implicated in mass death around the globe. (For all his insistence that he is a "precision tool", Mosley is tantalisingly imprecise about what it is that Bennet actually does.) As for what he's doing in the basement, it is, literally, abasement: he wants to be imprisoned by a black man, and even brings along a padlock from an old slave ship to provide the final lock on his cage.

Bennet turns out to be one of the world's unseen powerful men, maybe not evil in himself but in no way good and certainly a conduit for evil: "a precision tool", he puts it, implicated in mass death around the globe. (For all his insistence that he is a "precision tool", Mosley is tantalisingly imprecise about what it is that Bennet actually does.) As for what he's doing in the basement, it is, literally, abasement: he wants to be imprisoned by a black man, and even brings along a padlock from an old slave ship to provide the final lock on his cage.

At which point the novel becomes creepily gripping, confidently resonant. Other reviewers have flatly asserted that this is an allegorical novel; I am not so sure. It certainly beckons us to make allegorical sense of it, but I think we are also obliged to discard any such reading. It is, perhaps, more parable than allegory, and one which I am reluctant or unable to unpack. Besides, there is enough on the practical difficulties of keeping such a bargain to hold us rooted in the real world; although such difficulties include what kind of sense the jailer himself can make of the situation. Mosley has a fine sense for psychological complexity, delivered in the most stripped-down language.

Mosley has always, obviously, been finely attuned to matters of race; but he has also been interested in evil, or warped morality. Here the two concerns come together in a most bizarre and fascinating novel.

Our hero and narrator is Charles Blakey, a young black man who lives, perhaps improbably, in a 200-year-old house in (I think) Connecticut. It's in, as he puts it, "a secluded colored neighborhood", and while his house may be large and ancient, Blakey himself is coming apart at the seams: he is a shiftless, already washed-up man who can't hold down a job, drinks too much, alienates his friends with his puerile behaviour and, without handouts from his increasingly intolerant aunt, would lose the home that has been in his family for generations.

Our hero and narrator is Charles Blakey, a young black man who lives, perhaps improbably, in a 200-year-old house in (I think) Connecticut. It's in, as he puts it, "a secluded colored neighborhood", and while his house may be large and ancient, Blakey himself is coming apart at the seams: he is a shiftless, already washed-up man who can't hold down a job, drinks too much, alienates his friends with his puerile behaviour and, without handouts from his increasingly intolerant aunt, would lose the home that has been in his family for generations.

This picture of a man trapped by his own helpless indolence rings true; you feel that only a miracle, or a deus ex machina, could save him, and one arrives: a "small, bald-headed white man" (Serpent's Tail wisely does not reproduce the cover of the US Little, Brown edition, which appears to show, puzzlingly, a slightly built white man with a full head of hair), who offers him a huge sum of money to keep him imprisoned in his basement for a couple of months.

This picture of a man trapped by his own helpless indolence rings true; you feel that only a miracle, or a deus ex machina, could save him, and one arrives: a "small, bald-headed white man" (Serpent's Tail wisely does not reproduce the cover of the US Little, Brown edition, which appears to show, puzzlingly, a slightly built white man with a full head of hair), who offers him a huge sum of money to keep him imprisoned in his basement for a couple of months.It isn't until about halfway through the novel that the white man, Anniston Bennet, arrives for his incarceration. Until then we have had enough to be getting on with: Blakey's gradual decline, and then his determination to clean out the house, revealing centuries' worth of history. This is in itself a kind of redemption - a word Mosley pays particular attention to in the novel's closing pages - but Blakey still has some way to go.

Bennet turns out to be one of the world's unseen powerful men, maybe not evil in himself but in no way good and certainly a conduit for evil: "a precision tool", he puts it, implicated in mass death around the globe. (For all his insistence that he is a "precision tool", Mosley is tantalisingly imprecise about what it is that Bennet actually does.) As for what he's doing in the basement, it is, literally, abasement: he wants to be imprisoned by a black man, and even brings along a padlock from an old slave ship to provide the final lock on his cage.

Bennet turns out to be one of the world's unseen powerful men, maybe not evil in himself but in no way good and certainly a conduit for evil: "a precision tool", he puts it, implicated in mass death around the globe. (For all his insistence that he is a "precision tool", Mosley is tantalisingly imprecise about what it is that Bennet actually does.) As for what he's doing in the basement, it is, literally, abasement: he wants to be imprisoned by a black man, and even brings along a padlock from an old slave ship to provide the final lock on his cage.At which point the novel becomes creepily gripping, confidently resonant. Other reviewers have flatly asserted that this is an allegorical novel; I am not so sure. It certainly beckons us to make allegorical sense of it, but I think we are also obliged to discard any such reading. It is, perhaps, more parable than allegory, and one which I am reluctant or unable to unpack. Besides, there is enough on the practical difficulties of keeping such a bargain to hold us rooted in the real world; although such difficulties include what kind of sense the jailer himself can make of the situation. Mosley has a fine sense for psychological complexity, delivered in the most stripped-down language.

The voice he chooses for Blakey's narration is pitch-perfect: just articulate and fluent enough to keep readers happy, but not so much so that we feel that Mosley is trying to remind us that he's smarter than his creation. We know that, at least as far as Blakey's concerned, we're dealing with a human being, not an abstraction.

The voice he chooses for Blakey's narration is pitch-perfect: just articulate and fluent enough to keep readers happy, but not so much so that we feel that Mosley is trying to remind us that he's smarter than his creation. We know that, at least as far as Blakey's concerned, we're dealing with a human being, not an abstraction.